Co-written with Barry Evans and first published in February 2015

Introduction

Tesco has long been feted as a lean retailer and an early exponent of structured continuous improvement outside of manufacturing, so does its recent tribulations indicate that it has lost some of its lean sheen and indeed what does its experiences tell us about the nature of sustainable lean thinking in organisations?

Of course, Tesco is not the only retailer to be suffering, as in an apparent polarisation of retailing those in the middle market are feeling the squeeze – and recent consequences have included Morrison removing its chief executive and Sainsbury shedding 500 head office jobs. While Asda experienced its worst quarterly sales performance in at least 20 years in the 12 weeks to 4th January 2015, Aldi and Lidl increased sales by 22.6% and 15.1% respectively in the three months to January 2015 and Waitrose’s sales at established stores grew 2.8% in the five weeks to 3rd January, with grocery sales via Waitrose.com surging 26.3%.

While the UK grocery market is forecast to grow 16.3% from 2014 to 2019 (source: Institute of Grocery Distribution) key structural changes have been taking place and future growth will be driven by three principal areas: convenience, online and discounters. The shift in importance is illustrated strikingly in the table below, which shows the channel share of each £4 of market growth.

Channel Share of each £4 of market growth

Superstores and hypermarkets: -£0.42

Small supermarkets: £0.03

Other retailers:-£0.01

Convenience: £1.62

Discounters: £1.49

Online: £1.29

TOTAL £4.00

Being able to anticipate market tends and changes in customer value has been central to Tesco’s success over the last two decades, so has Tesco lost its ability to understand such shifts in market forces? It was the first major multiple to see the potential of two of these significant growth areas – namely convenience stores and online grocery sales and it began operating in these areas in late 1990’s. However, it appears not to have anticipated perhaps the most critical of these – the growth of discounting and associated changes in the consumer value proposition.

What Makes a Company Lean?

Unsurprisingly, there is no single measure that simply indicates that a company is, or is not, lean – not least because lean proponents have a variety of definitions of lean thinking which makes the task difficult.

However, what is generally accepted is that being lean is not about the propensity to use specific lean tools and techniques, the number of PDCA cycles undertaken or the number of CI experts or black belts employed, though these may be characteristics of lean companies. Measures of leanness surely must be expressed in terms of value and the ability of the company to deliver maximum customer value with the minimum resources, closely linked to its core purpose.

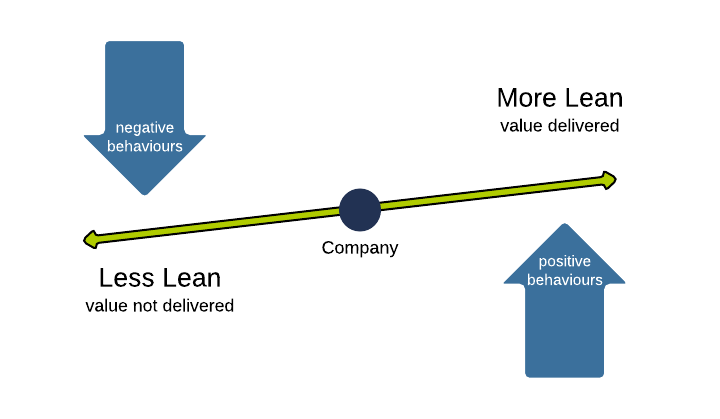

It is also helpful to view leanness not as an either-or condition, but rather as a spectrum or continuum, along which companies can move one way or another depending on their behaviours and performance in delivering value.

A key point to note about the spectrum is that it is lies at an angle, suggesting that a company will slide to the less-lean left if it does not maintain its ability to identify and deliver value and purposively adopt the right supporting behaviours.

Tesco’s lean credentials are evidenced by several factors. Driven by former chief executive Terry Leahy, it was an early adopter of lean thinking in the 1990’s, which was primarily focussed on cutting costs and removing waste from its supply chain, which lead to significant savings and improvements.

It pronounced that the seminal Womack & Jones book Lean Thinking was one of three that informed its mantra, along with Loyalty by Reichheld and Simplicity by de Bono. It adopted several lean techniques, notably the Tesco Steering Wheel as a policy deployment vehicle and perhaps most importantly developed a passion for driving customer value, illustrated by its better-simpler-cheaper test for any potential innovation or improvement.

However, its profitability, sales increase and market share growth over a prolonged period are arguably the critical indicators in its ability to deliver customer value and therefore meet the lean company test. From 1992 to 2011 its average annual profit growth was 12.5%, (which had slipped to -3.3% 2012 to 2014) with its comparative sales growth figures 12.3% and 1.5%.

Tesco, it is argued, has slid towards the less lean end of the spectrum, as it has become less effective in its ability to understand and deliver customer value. It has, not doubt, maintained lean activities, such as been taking waste out of processes, deploying strategy, improving flow and solving problems, though these alone are not enough to arrest the slide.

Tesco & Customer Value

Tesco under CEO’s MacLaurin and particularly Leahy had an excellent track record of working tirelessly to understand and deliver what customers valued. They developed many mechanisms to understand customer wants, such as Clubcard data, customer panels and market research.

Thus they strove to keep abreast of what customers wanted (or did not want) and crucially aimed to deliver this through focused company-wide change programmes, with all functions focused on what they had to do to deliver their part of it. No localised versions were permitted, but everyone was encouraged to feed in ideas for improvement – with the best chosen for development and company-wide roll-out.

These were evaluated and the best were developed into operable methods and implemented company wide. This delivered huge benefits, as each operation in distribution centre store order picking, store shelf replenishment, checkout scanning of customer baskets and so on is repeated literally millions of times each year, so a small improvement in each operation cascades through to significant bottom line gain. The better-simpler-cheaper failsafe ensured no unintended consequences, since improvements must have a positive impact on all three.

Of course, the delivery of customer value is very simple to describe, though not necessarily easy to deliver and making and keeping things simple takes hard, focused effort to deliver and sustain.

Factors Underlying Tesco’s Slide

The root causes of the decline in Tesco’s performance over the last two years and its ability to deliver value to customers are likely to be a combination of several factors, both external and internal. The relative importance of each is difficult to gauge and it is their interaction together that is important.

Externally, the financial crisis of 2008 had a negative impact on earnings and accelerated the rise of polarised custom – the discounters and high-end – which ushered a return to prominence of clear value propositions, such as promotions, and three-for-two, rather than an overemphasis on retail theatre. Changing consumer shopping habits, particularly the growth of online and convenience have also been important.

Internally, there are factors that may have contributed to losing sight of their customer. These include an over focus on technological changes and too much emphasis on extended supply chains, where low cost is chased through efficiency at the expense of effective provision of provenance and erosion of core values, which undermined customers’ trust. The horsemeat scandal was a case in point and the accounting issues and overstatement of profits a symptom of this malaise.

Terry Leahy warned in late the late 1990’s – the years of plenty – that Tesco’s biggest enemy was complacency. Being complacent, in lean terms, can be linked a loss of clarity of purpose, so did Tesco fall into this trap? With a high market share in a mature core home market, inevitably it began to look for other opportunities, to satisfy stakeholder demands for even more growth and bigger dividends and not least provide exciting new challenges for ambitious executives.

Consequently, there was diversification into a wide range of activities, including video-on-demand, financial services, brown and white goods, mobile phones, broadband and so on, as well as substantial international retail expansion. If you accept, as Disraeli said, that the secret to success is constancy of purpose, then the loss of clarity of purpose will inevitably lead a range of problems, not least in maintaining an understanding of customer value.

The Road to Lean Redemption?

The arrival of Dave Lewis, Tesco’s first ever externally recruited CEO in September 2014, has heralded a number of fundamental changes in direction. Under Lewis, who has a strong consumer brand pedigree, Tesco claims it will re-focus on what the customer values by taking it back to its core purpose and focusing on price, availability and service. It aimed to improve in store service by recruiting additional staff and has disposed of some of its technological offers.

Early indications of the impact of the new CEO’s approach on trading performance and share price have been positive and it is worth noting that Tesco’s financial performance is still delivering profits in excess of £1 billion – the only UK retailer achieving this – so the level of crisis is relative should be viewed in this context.

Summary

On one level, Tesco’s recent story can be part explained by a well-known marketing paradigm termed the Wheel of Retailing.

This contends that retailers enter the market at the low end and make immediate market share gains by offering low prices made possible by very efficient operations. Overtime, these retailers become increasingly bloated by letting their costs and margins increase. Their success leads them to upgrade their facilities and diversify, increasing their costs and forcing them to raise prices. Eventually, the new retailers become like those they replaced and the cycle begins again when still newer types of retail forms evolve with lower costs and prices. Loss of core purpose and lack of understanding of customer value lie at the heart of explaining the cycle.

Tesco under MacLaurin and Leahy were very successful and the latter’s obsessive focus on the customer and what they valued gave a powerful system purpose that Tesco followed. Many innovative changes were implemented and made possible by Tesco’s development of an increasingly capable supply chain.

At some point Tesco lost sight of the source of its growth, exacerbated by a number of self-induced and external factors including, a purpose that became more opaque and thus less meaningful, technology-based priorities seen as more important than delivering a customer service and possibly leadership complacency – deemed by Leahy to be Tesco’s greatest threat. In BBC Panorama programme in January 2015, Leahy said that he blamed poor leadership by his successors as the key factor, though it can be argued that several of the seeds were sewn during his tenure at the top.

Undoubtedly, the revolutionary market change driven by the financial crisis and the consequent market polarisation had a major impact that exacerbated the effect of the negative internal factors that resulted in the recent difficult years for Tesco. This is when significant changes in customer value occurred that, in fairness, were very difficult to predict.

The corporate graveyard is littered with the headstones of once great companies that, for whatever reason, at some point failed to deliver value to their customers and shuffled out of corporate existence. Sometimes this was due to internal factors or short product life cycles, sometimes due to external forces such as dramatic technological, social or economic changes.

Of course, it is notoriously hard to always know what customers want; three quarters of new products are said to fail, customers keep changing their expectations, they often do not know what that want and buy on emotion as well as reason. Henry Ford knew this when he said if I‘d asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.

The point is that occasionally companies will be faced with significant shifts in customer behaviour that they did not, or could not, predict. The ability to adapt to such changes is therefore critical to survival. This adaption will involve restating its purpose based around its core competences so as to engage with its customers and recapture the ability to understand value. The indications are that the new management at Tesco is returning to a customer-focused approach, getting back to basics and clarifying purpose. These, together with re-building positive behaviours, mean it has the opportunity to move it in the right direction along the lean spectrum and reconnect with its customers in delivering the value they demand.