Introduction

For well over a decade continuous improvement approaches have been formally applied in the public sector in the UK and elsewhere, in an attempt to improve service quality and streamline processes, often in response to cuts in public expenditure budgets imposed by governments.

Many public services in the UK – including defence, healthcare, police, higher education, central and local government – have now, to a greater or lesser extent, implemented continuous improvement (CI) programmes of various shapes and sizes. However, while there are numerous examples of successful initiatives at a process level, questions remain about whether real systemic changes are being made that will produce the long term sustainable CI culture desired.

This article examines the nature of the lean thinking that has been embraced and calls for a debate on the development of a new definition of lean for public services. It contends that the adoption of an unadapted lean approach that is primarily geared for the private competitive market has meant that public service organisations have misunderstood the nature of value in the public sector, which has created counter-productive distractions and raises issues on lean’s ability to help engineer long term, systemic change.

Lean & Competitive Advantage

This discussion about lean’s role in improving public services starts with examining the purpose of lean thinking and lean methods. The roots of contemporary lean thinking can be traced to the development of the Toyota Production System (TPS) after the second world war and for Taiichi Ohno – Toyota’s chief engineer and architect of the system – it can reasonably be deduced that the ultimate aim of TPS was to create competitive advantage for Toyota, so that buyers of cars chose a Toyota model over those of its competitors.

This was achieved by producing a vehicle that delivered clear value for customers in terms of its cost, quality, reliability, design, performance and so on. The production system’s design was influenced by a post-war environment characterised by shortages and constraints and TPS’s particular ability was to be effective in removing waste from processes and creating flow, thus enhancing customer value adding activities and so creating additional capacity that could be used to sell more cars and expand the business.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The essence of the free market model is that the customer is able to choose among competing offerings and will part with his or her money to the producer that can deliver the greatest perceived value. This classic model positions the private consumer – the customer – as the arbiter of value, whose decisions will ensure that competing businesses will strive to be more effective in meeting his or her needs and delivering the right products at the right prices.

Marketisation of Public Services

UK public policy in the 1980’s was dominated by the neo-liberal thinking of Prime Minister Thatcher and her Conservative governments, which placed a strong emphasis on the virtues of competition and a view that the size and influence of the state should be reduced. Public services were considered bloated, with inherent inefficiencies and a drag on economic growth.

New Public Management (NPM) emerged as the supporting doctrine to this policy, that advocated the imposition in the public sector of management techniques and practices drawn mainly from the private sector, as according to NPM greater market orientation would lead to better cost-efficiency, with public servants becoming responsive to customers, rather than clients and constituents, with the mechanisms for achieving policy objectives being market driven.

NPM reforms shifted the emphasis from traditional public administration to public management and this included decentralisation and devolution of budgets and control, the increasing use of markets and competition in the provision of public services (e.g., contracting out and other market-type mechanisms), and increasing emphasis on performance, outputs and a customer orientation.

Some parts of the public sector left it completely through privatisations, such as utilities, transportation and telecommunications; semi-autonomous agencies were created, such as the DVLA and outsourcing major capital projects through private finance initiatives became common.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The Citizen’s Charter was replaced in 2005 by the Customer Service Excellence standard, led by the Cabinet Office, which aimed to “bring professional, high-level customer service concepts into common currency with every customer service by offering a unique improvement tool to help those delivering services put their customers at the core of what they do”. This offered public sector organisations the opportunity to be recognised for achieving Customer Service Excellence, assessed against five criteria, which included ‘customer insight’. To date, several hundred public sector organisations are listed on its website as having achieved Customer Service Excellence.

When the formalised and packaged versions of contemporary lean thinking and CI appeared from the 1990’s, it was a logical step for public sector organisations to adopt these approaches as part of the NPM agenda, especially as continuous improvement was integral to initiatives such as Citizen’s Charter and Customer Service Excellence, as these could help them cope with increasing demand for their services, coupled with reducing budgets and the drive to be customer focussed. Techniques to reduce waste and costs were particularly attractive, even if the resultant released capacity could rarely be used to ‘grow the business’ as it could be in the private sector.

Thus public services readily and enthusiastically embraced all aspects of lean philosophy, integral to which was a market orientation, where the identification and delivery of customer value was paramount.

The Nature of Value & the Customer in Public Services

A process is a process, whether it is in the private or public sector and so it can be argued that process thinking, as defined by System Thinking advocates such as W Edwards Deming, is equally applicable to both, since waste removal, improving quality, reducing lead time and enhancing flow are universal aims.

So while it seems reasonable for public services to use the techniques at a process level to produce some public good, it is argued that by including an explicit customer orientation, it leads to a range of problems.

A key issue is the NPM contention that there are customers in public services for whom value is identified and then delivered. The classic characteristics of customers is their ability to choose between different products and suppliers and spend their money according to the offering that delivers the greatest perceived value. However, in this sense, a customer rarely exists in a public sector context.

Instead, according to writers such as Teeuwen, they are citizens, who can have several roles at different times, including that of user, subject, voter and partner; occasionally, the citizen can be a customer, such as when choosing among transportation options, but it is not the dominant role. To this list could be added patient and prisoner and even obligatee, as Mark Moore describes taxpayers, who clearly have no individual say in taxation, but simply an obligation to pay up. In most of the roles, the individual citizen does not ‘specify the value that is to be delivered’ and has no choice in service provider.

Therefore, it is suggested that the concept of an individual customer deciding on what constitutes value is flawed in a public sector context. This can distort service design, lead to the use of inappropriate or unhelpful measurements with the numerical quantification of quality through targets, create expectations in citizens that cannot be met (leading to frustration and dissatisfaction) and lead to confusion regarding the true purpose of the function or service.

Public Value, not Customer Value

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Identifying what value to produce for a public service therefore has little to do with an examination of an individual’s needs and preferences. There is also no requirement to win custom and market share through a variety of product delighters, innovations and exceptional customer service.

The notion of public value has echoes of the 19th century Utilitarianism philosophy of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which stated that the goal of human conduct, laws, and institutions should be to produce the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Other significant contributors to the public service value debate in the UK include John Benington at Warwick University (who has collaborated with Moore) and John Seddon, whose CHECK improvement methodology focuses on the need to identify purpose as a prime initial task in service improvement, rather than go down the customer/value route. Identifying purpose appears to have strong resonance with public value.

Identifying public value is not an easy proposition and because decisions are almost always about how to allocate scarce resources, there will be compromise and invariably an individual’s demands will be subordinate to those of society in general.

Moore contends that the pursuit of public value aims requires the support of key external stakeholders, such as government, partners, users, interest groups and donors. Public sector decision makers must be accountable to these groups and to engage them in an ongoing dialogue and build a coalition of support to create this platform of legitimacy.

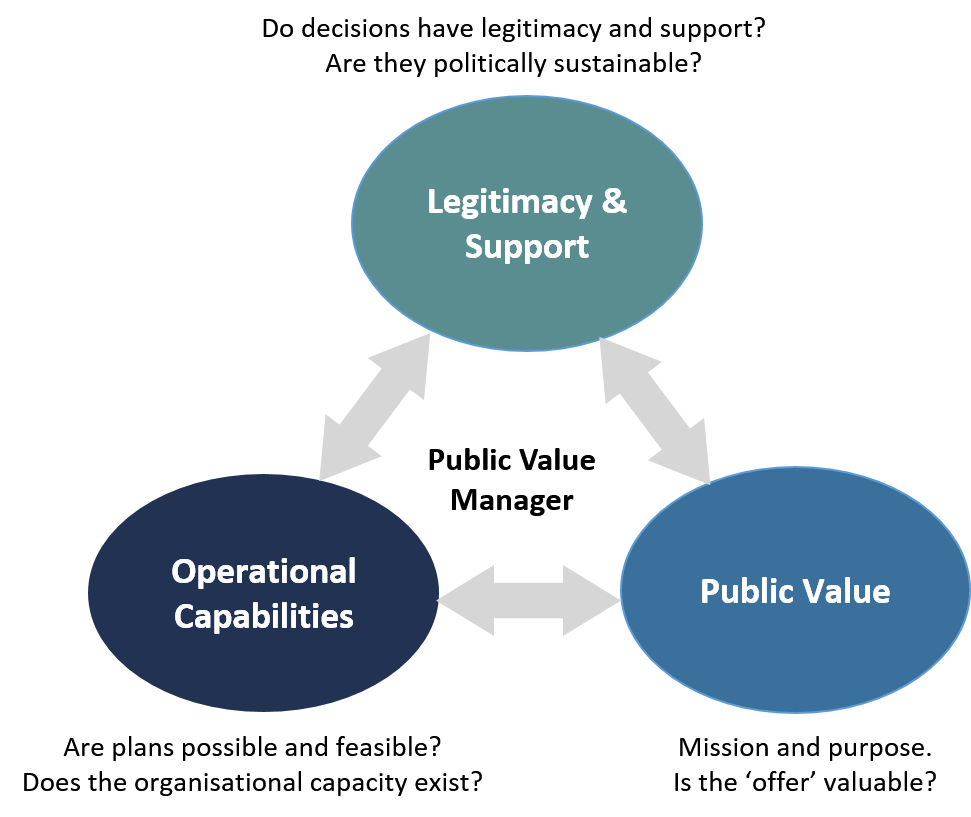

He describes a “strategic triangle”, which represents the dimensions that the public service manager needs to consider in developing a course of action, comprising of the authorising or political environment (legitimacy and support), the operational capacity and the public value (purpose). The proposition in the strategic triangle is that purpose, capacity and legitimacy must be aligned in order to provide the public manager with the necessary authority to create public value through a particular course of action.

Service v. Value

As a result of the NPM agenda, citizens have been led to believe that they are customers of public services, just like they are customers of private businesses and therefore have the same service expectations of public services as when they transact with, for example, retailers John Lewis or Amazon. Similarly, public sector employees have been encouraged to treat the recipients of their services like private sector customers.

This does not mean that public services should not strive to deliver a productive and positive experience to its users, patients, obligatees etc., especially as the outcome of effective process thinking should supply exactly that. As taxpayers, citizens have a reasonable expectation to receive quick, effective and courteous service, but this may have little to do with delivering public value or in achieving its prime purpose.

Indeed, public value is often at odds with private value; consider airport runway expansion in the south east of England, the route of the HS2 train from London to Birmingham, the creation of dedicated cancer drug funds, the gritting of roads in icy conditions and the building of flood defences.

Many public service measures, such as in healthcare, have an explicit customer service orientation and a significant amount of debate and political energy is spent scrutinising these. This is not to say that waiting times for treatment or answering a phone call are not relevant, but that they distract from the important question of assessing and understanding the public value that the particular service should strive to deliver.

HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) regularly receives significant media and public criticism and a report by the National Audit Office in 2012 into its customer service performance concluded that “while the department has made some welcome improvements to its arrangements for answering calls from the public, its current performance represents poor value for money for customers.”

In 2014-15, HMRC collected a record £518 billion in total tax revenues, employing some 65,000 people. In 2005-06, it collected £404 billion with around 104,000 staff; this means that over a decade it has collected 25% more revenue with 38% fewer staff. It has also made cost savings of £991 million over the past four years. HMRC delivers public value by maximising the tax take using as few as resources as practical, though clearly it does have service obligations to its users.

Interestingly, the National Audit Office report comments that “HMRC faces difficult decisions about whether it should aspire to meet the service performance standards of a commercial organization. It could do only by spending significantly more money or becoming substantially more cost effective.” This is the nub of the dilemma faced by many public services and a key question is whether it should indeed strive to be like a commercial organisation and expend more and more resources in doing so. However, service should not be confused with value.

In the private sector there usually a clear relationship between the price paid and the service received. The Kano model refers to performance or linear attributes of an offering – ‘more is better’ – where increased functionality or quality of execution will result in increased customer satisfaction. For example, we can choose the speed of delivery of an online purchase by selecting either the free (3 to 5 days), standard (2 days) or premium (next day) service and we will make a conscious decision to pay for the one we desire.

This scenario takes place in some UK public services, such as obtaining a new passport, where there are differently priced one week Fast Track service and one day Premium service, though in most public services a direct service-price relationship does not exist.

Conclusions & Future Discussion

The classic lean thinking approach that emerged from TPS is ideally suited to organisations operating in a competitive market environment because of its focus on customer value, its ability to help create competitive advantage, grow market share and ultimately enhance shareholder value. This article contends that the wholesale adoption of this approach by public services is inappropriate, as it does not recognise the difference between private value and public value.

Just as there was a debate in the early 2000’s about whether the lean thinking that was developed and used in manufacturing was suitable for service environments, there needs to be a debate about how it should be adapted for public services and in particular the move towards adopting a public value perspective.

The following suggestions can help inform this debate:

- Lean practitioners in public services should move away from an overt focus on individual customers and the value they demand. Those using Womack and Jones’ first lean principle (‘specify value from the standpoint of the customer’) should adapt it so that the emphasis is on specifying public value that is to be delivered, linked to the purpose of the organisation.

- There needs to be a redefinition of what it means to be a customer of public services; while it is probably too late and counter-productive to abandon the term customer, a new specific public service lean vocabulary will help provide clarification. As Mark Moore comments “the individual who matters is not a person who thinks of themselves as a customer, but as a citizen”.

- Lean leadership in the public sector should primarily focus on understanding and identifying public value. Mangers need to focus specifying the public value that they are trying to deliver and make it clear that this can be different or even in opposition to private value. The key question that a lean manager needs to ask, according to Benington and Moore, is not what does the public most value? but what adds most value to the public sphere?

- The recipients of public services – citizens – need to be educated as to what they can reasonably expect from the public sector in terms of service levels and understand that when they ‘consume’ public services, they are not customers in the same way as when they consume in the private market; they do not have the same rights, advantages or privileges. The level of service provided in delivering services needs to be balanced against the cost of providing it. Citizens also need to understand that public value will sometimes be at odds with private value.

- Public services generally do not present products to a market in the same way that private companies do, the latter then plotting the optimum value stream for delivery to the customer. Rather, they usually wait for demand for services and react; this suggests there should be less emphasis on value stream management and more on demand analysis and management – with a greater emphasis on understanding the nature of the demand (quantity and quality), proactively attempting to limit and control it in many circumstances.

Few would argue that effectively applied process thinking cannot have a positive role to play in improving public services and it is contended that adopting a public value perspective will enhance its overall impact.

But the shift from private value to public value is not without its challenges; several decades of NPM thinking has created a mindset that may be difficult to change and moving to more utilitarian position in an age of individualism may be a daunting prospect. Mark Moore says that a key reason why public value is a challenging idea is because it brings us out of the world of the individual and back into the world of interdependence and the collective; and that, he claims, “runs contrary to the direction that everyone seems to be going in”.

References & Further Reading

Download a pdf version of this article

Watch a Mark Moore video in the LCS website Video area.

Building our Future: Transforming the way HMRC serves the UK (2015), HMRC

Creating Public Value (1995), Mark Moore

Customer Service Excellence website: www.customerserviceexcellence.uk.com

Freedom from Command & Control (2005), John Seddon

Lean for the Public Sector (2011), Teeuwen

Lean Thinking (1995), Womack & Jones

National Archives, Charter Mark website: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20040104233104/cabinetoffice.gov.uk/chartermark/

National Audit office website: www.nao.org.uk

Public Sector Management (2012) Norman Flynn

Public Value: Theory and Practice Paperback (2010), Benington & Moore

Service Systems Toolbox (2012), John Bicheno

Systems Thinking in the Public Sector (2010), John Seddon

The Guardian: www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/02/narcissism-epidemic-self-obsession-attention-seeking-oversharing

The Machine that Changed the World (1990), Womack, Jones & Roos