“The trouble with us is that we’ve got no corporate memory.”

I’ve heard this statement in various forms from a variety of different people I’ve worked with over the years. The starkest version came from a senior officer in a police force. He was referring to the fact that his organisation kept trying new improvement initiatives, which would never fully achieve their potential.

The projects made mistakes, progress stalled and the initiative would ultimately fade away into insignificance. Then, after a few years, something similar would be instigated, with no attempt to first understand why things didn’t work previously and put mechanisms in place to prevent them happening again.

A critical element of the problem is that even though an organisation keeps making the same mistakes that doesn’t mean its employees have forgotten what those errors were. As the senior officer recounted, he remembered what did and didn’t work – it was the organisation that didn’t. The ultimate result? A negative organisational culture hostile to change.

Many academics have sought to address this problem. Peter Senge, for example, in his book The Fifth Discipline highlights the importance of being a learning organisation. One that is constantly open to new ideas and innovation, and builds upon experience to become quicker, smarter and more knowledgeable. He suggests five different elements of a learning organisation:

- Systems thinking

- Personal mastery

- Mental models

- Building a shared vision

- Team learning

He is, of course, not the only voice to suggest that learning is key to success. W. Edwards Deming and Walter A. Shewhart introduced the ‘four-step management method’ to business in the early twentieth century. We can recognise this process as a ‘scientific’ approach to work.

- Plan: What do we want to change

- Do: Make the change

- Study/check: Did it achieve what we wanted?

- Act: If it did make sure that everyone benefits and embed the learning. If it didn’t, what should we try next time?

If discipline is applied to the process, the organisation ‘learns’.

Data is the key driver of this scientific process. Much of what many improvement methodologies offer, including Lean, Six Sigma and Agile, is mechanisms to collect, analyse and interpret information and data, so that managers can see what is happening, make a change and learn. Steven Spear and H. Kent Bowen are very specific about what this involves in their paper Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. They talk about organisational learning taking place “at the lowest level” by those who do the work, under the guidance of a teacher, preferably using the Socratic method.

In my work, I see too many organisations that have put insufficient focus, effort, time and space into this learning process. The organisation understands (to varying degrees) that it needs to worry about its end-to-end processes and ultimately to keep improving them, but it often forgets about ‘creating an improvement process’ within which to examine the work process.

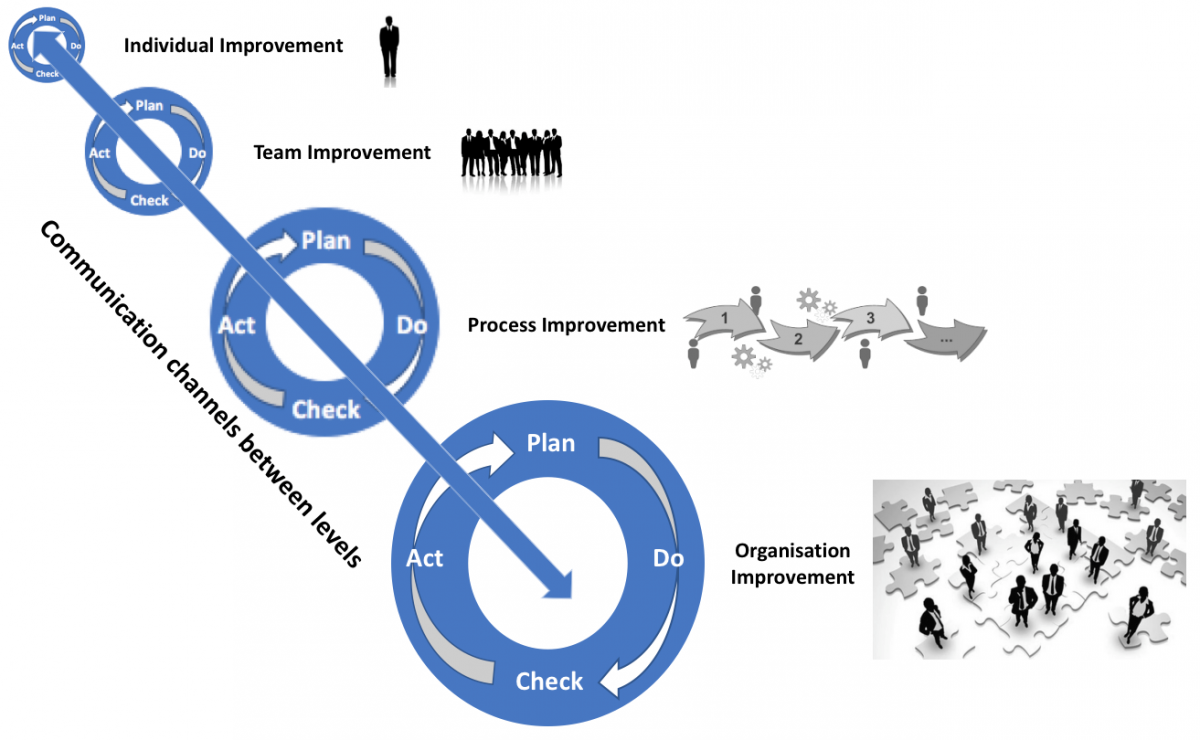

Critically, an improvement process is needed not only at a process level but at a team level, and even at an individual level. Above these levels of improvement, the organisation itself needs to examine how it works as a system, and improve how it sees and manages itself, how it learns.

I’ve tried to illustrate this concept in the graphic below, using the scientific ‘Plan, Do, Check, Act’ cycle as an iterative loop of learning, which must occur at different levels and scales.

What’s important is that there is a formalised improvement process for each of the levels. That each level is given time within their working day/week/month to engage in the improvement process and that they understand how to use the relevant improvement tools within each level. One of the most important features of this layered approach to organisational improvement is that there is an actual process of communication between the levels.

For example, if a team is experiencing difficulties with an element of work, then they should have the time and tools to scientifically work out what is going wrong and a communication channel to discuss problems with individuals. If, however, the trouble is occurring outside of the team, then they should know how to ‘kick up’ the investigation of that problem to the ‘process’ level. Too often improvement, and therefore learning, happens in isolation and not part of a connected system of organisational change.

Thinking about companies in this way enables managers to appreciate that it’s not enough to simply manage processes of work. They must also manage processes of improvement and learning.

This article originally featured on Hewlett Packard BVEX blog